The Jefferson County, Alabama, bankruptcy case was slightly more unusual than other municipal bankruptcies, in which the financial downturn severely impacted a municipality’s ability to meet its expenditures.

The bankruptcy case of Jefferson County, Alabama, was the epitome of corruption and bribery amongst elected officials, contractors, county employees, and bankers involved in the county’s sewer-related debt issuance. This one public work project, often referred to as “the Taj Mahal” of sewage systems, became the epicenter that led to the county filing for bankruptcy and, ultimately, two dozen people, including elected officials, contractors and county employees went to jail for bribery and fraud charges.

In this article, we will take a closer look at the Jefferson County, Alabama, bankruptcy case and what the bankruptcy settlement means for investors and creditors.

Be sure to check out our Education section to learn more about municipal bonds.

What Leads to a Municipal Bankruptcy

When a local government is struggling with its crippling debts and is unable to meet its financial obligations, it can seek protection under Chapter 9 bankruptcy from its creditors while developing a comprehensive plan to put forward for adjusting its debts. This plan mainly includes a way to reorganize the municipality’s debts and potentially extend the maturities to lower its debt service payments and/or possibly refinance its debt obligations to lessen the financial burden.

At an individual level, this may sound similar to a mortgage loan refinancing or loan modification that will prolong the term of the loans, which, in turn, decreases the monthly payments. However, unlike bankruptcy laws reserved for individuals, there is no provision under the Chapter 9 bankruptcy code that warrants the liquidation of assets of the municipality and distribution of the proceeds to investors or creditors.

Under Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection, the municipality files for a petition, drafts a plan of debt adjustments and follows this plan. All these stages are approved by the bankruptcy court and require monitoring to ensure proper adherence to the plan of adjustment.

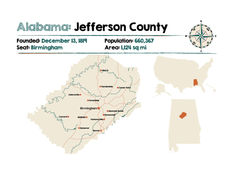

When Jefferson County, Alabama, filed for its bankruptcy in November 2011, it became the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

Don’t forget to check out our municipal bond screener here to find bonds meeting your specific investment criteria.

The case of Jefferson County, Alabama

The entire bankruptcy case entailed a debt amount of $4.3 billion and a majority of this debt was incurred due to the need to expand and repair the sewer system after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) accused the county of dumping raw sewage into nearby rivers.

Initially, to pay for the repairs, Jefferson County began borrowing money and refinancing old debt, issuing more than $3 billion in warrants and interest-rate swaps by 2003.

In this expansion of its sewer system project, the county tried to bore a giant tunnel beneath the Cahaba River, which is Birmingham’s main source of drinking water. But the tunnel was so unstable that the endeavor was abandoned. The county spent millions just to extract the boring machine, which had become entombed underground. Mary Williams Walsh of The New York Times sums up the findings of John S. Young with Municipal Analysts Group of New York perfectly by stating the following, “That cost $19 million, now it’s called ‘the Tunnel to Nowhere.’ ”

All these efforts didn’t result in fixing the sewer system and the project required more funding, which ultimately would’ve required additional revenues to issue more debt to handle the situation and comply with EPA findings.

In dire need of additional funding, the county officials turned to J.P.Morgan Chase and agreed to a bond deal, with terms that included complicated interest rate swaps. Those swaps blew up during the financial crisis of 2008, leaving the county with even more debt than it had started with. In addition, as mentioned earlier, the project and its financing led to a variety of criminal and civil charges, with several officials and others receiving prison time. In one case, Larry Langford, a former president of the Jefferson County Commission and former mayor of Birmingham, was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Click here to learn more about the municipal debt due diligence process.

The Bankruptcy Settlement

As the county exited bankruptcy around June 2018, the settlement entailed $1.8 billion of debt issuance to refinance about $3.2 billion of sewer debt issued earlier on. This settlement included J.P.Morgan Chase and other creditors. Furthermore, to ensure the continuity of revenues, the sewer rates were agreed to be raised by 7.9% annually for the next four years and 3.5% afterward.

In regard to the final settlement between the county and J.P.Morgan, Mary Williams Walsh of The New York Times also stated that although J.P.Morgan, in its settlement, let the county out of its swaps deal, the county’s underlying debt remains outstanding. Today, the county is effectively shut out of the muni bond market and is coasting on reserves, further delaying work on sewers that don’t function properly.

You can read more about Jefferson County, Alabama’s, plan of adjustment here.

The Bottom Line

Municipal bankruptcies often share a common thread of overall financial downturn; however, there is an array of other reasons that can exacerbate the financial position of any municipality during a financial downturn. This particular case was due to financial mismanagement of public funds, public trust and bribery in the case of Jefferson County, Alabama.

The county’s bankruptcy case eventually cost the taxpayers over $30 million in legal and advisor costs.

Sign up for our free newsletter to get the latest news on municipal bonds delivered to your inbox.

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements expressed in this article are for informational purposes only and are not intended to provide investment advice or guidance in any way and do not represent a solicitation to buy, sell or hold any of the securities mentioned. Opinions and statements expressed reflect only the view or judgement of the author(s) at the time of publication and are subject to change without notice. Information has been derived from sources deemed to be reliable, the reliability of which is not guaranteed. Readers are encouraged to obtain official statements and other disclosure documents on their own and/or to consult with their own investment professionals and advisers prior to making any investment decisions.